Inspiration trip to Japan

This was a special trip as I’ve always had an interest in Japanese art and, as many of you know, I work a lot with Japanese fabrics as well as design elements. It’s also been years since I’ve been on a solo holiday to a new place and at a time when I had been facing several challenges, the extra energy generated from such a trip was well-appreciated.

So here’s my version of Tokyo and Kyoto, with a design-oriented itinerary that included museums, workshops, mountains, lakes, gardens, shrines, temples, and shops!

TOKYO & KYOTO

This 6-day trip started at the Kiyosumi Gardens in Tokyo, and ended at the Kiyomizu-dera Temple in Kyoto.

In between, there was a half-day trip to the Itchiku Kubota Museum located at Lake Kawaguchiko with a view of Mt. Fuji. About the Itchiku Kubota Museum — this is a museum dedicated to and built by Itchiku Kubota, a kimono maker known for his reinvention of tsujigahana (a dyeing and knotting technique that results in intricate patterns).

Additionally, I also did a half-day trip to the Miho Museum, which focuses on East Asian art (calligraphy, ceramics, lacquerware). Situated in the mountains of Shigaraki in the Shiga Prefecture, the pathway to the museum, which features a garden walkway, a tunnel, and a bridge, was in itself a journey that blends nature, architecture and art.

From Tokyo, I caught a bullet train to Kyoto. Unlike Tokyo which is fast-paced and modern, Kyoto is slow-paced, retains a historical charm, surrounded by mountain ranges. I hesitate to call Kyoto “traditional”. Rather, I would say that in Kyoto, one can clearly trace the connections between modern and traditional architecture / fashion. From shrines to contemporary buildings, from shibori to Issey Miyake, Kyoto presents a seamless juxtaposition of old and new. In fact, I would recommend Kyoto to designers who wish to increase their understanding of Japanese techniques, materials and approaches.

Overall, what impressed me the most about Japan is the level of care and consideration for the environment — a trait that stems from Shinto beliefs of respect and reverence for nature. This results in a harmonious integration of the natural world and man-made objects, which in turn evokes calm. This sense of harmony is most apparent in Japanese gardens but also, uniquely, in commercial spaces, down to the design and manufacturing of products.

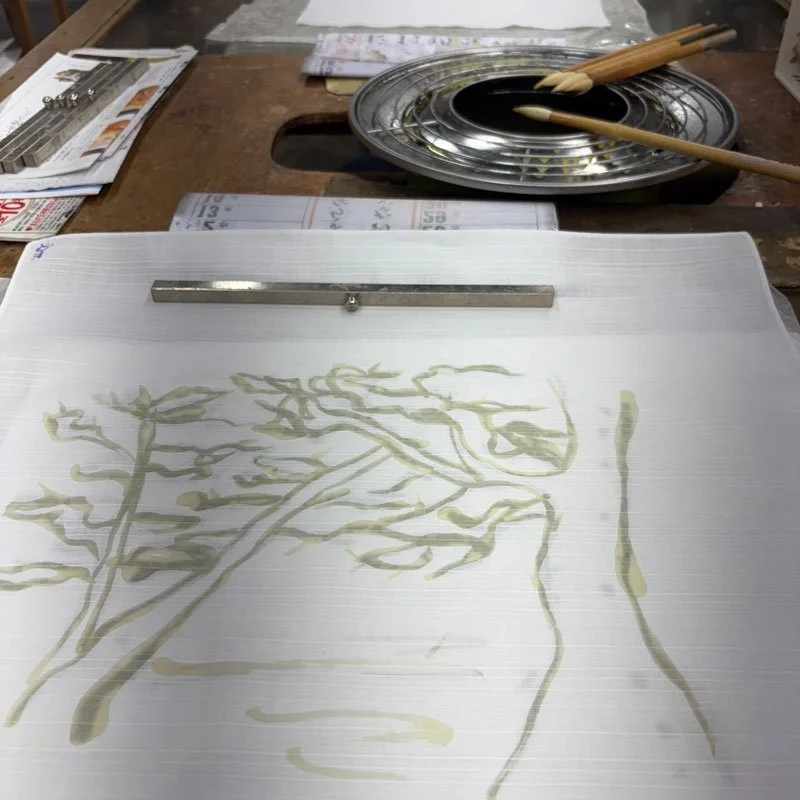

WAX-RESIST DYEING (BATIK) WORKSHOP

As you see in the above images, I used hot wax to paint a pattern on a piece of unbleached cotton. The fabric is then dyed, washed in hot water several times to remove impurities, and steamed to dry. The area applied with wax is blocked out and remains white. What I learnt is how the treatment of wax can affect the depth of the pattern — the more layers of wax applied, the more opaque the resist becomes; on the other hand, just 1 layer of wax creates a more translucent pattern.

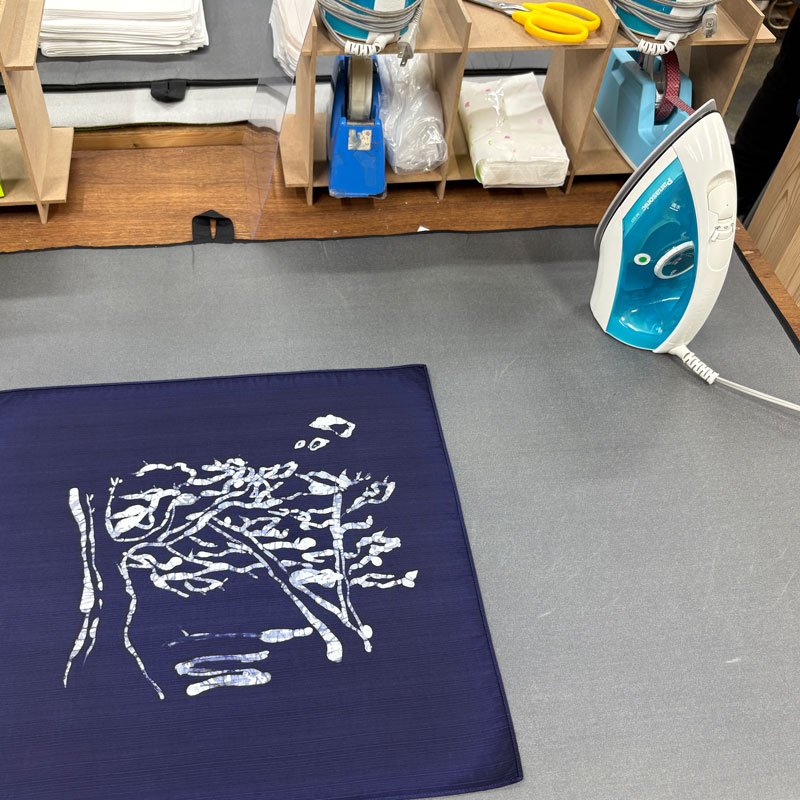

SHIBORI (TIE-DYEING) WORKSHOP

I was initially hesitant to take up this workshop because I (like many others) had several assumptions about tie-dyeing. I decided to do it anyway because I thought I could at least make a scarf for my mum. This turned out to be the most eye-opening experience of my trip as I discovered the scope of shibori.

The first 3 images show a basic itajime shibori (folding and blocking a pattern with shapes). First I fold the unbleached silk into a triangle. Next, I dye the fabric in green while using a circular-shaped block. Then, I dye the fabric in gray using a square-shaped block.

After this initial dye experiment, I was then introduced to different shibori knotting, tying, and stitching techniques. I learnt about how the types of thread used in knotting (for e.g. a linen thread naturally shrinks in hot dye and thus causes the fabric to pucker) affect the fabric texture, and how shibori artisans plan out their designs. What is fascinating about using shibori to create a complex pattern (e.g. a landscape pattern with several motifs and color gradation like the final 2 images) is that the artisan has to simultaneously plan and execute the color, texture and design. This is unlike most forms of textile design where perhaps the fabric is first dyed, then texturized, or vice versa. Finally, I learnt that traditional shibori uses only natural fibers. This is interesting because in certain types of shibori, the “stiffness” of texture adds a completely different dimension to silk which is typically soft and fluid.

You know it’s been a good trip when you leave with the excitement of getting back to work!